skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I'm sure by now, most of you have either binge-listened or at least heard of the podcast phenomena that is Serial. Birthed from the wonderful nerdtopia radio series This American Life, Serial focuses on a single story, reexamining the details and the people involved, done with the intent of providing fresh new answers. Inevitably, it creates more questions and gives us all plenty to talk about. The first season -- free for download off iTunes or the Serial site -- was about a murder of a young high school girl named Hae Min Lee in 1999, in Baltimore, Maryland. Adnan Syed, her ex-boyfriend, was investigated based on a friend, Jay, who claimed Syed came to him to help bury Lee's body. Syed refutes Jay's account and says Jay's story is a total fabrication, he had nothing to do with her murder, and a confusing web of accounts over his whereabouts and motives are all explored in the 12-part podcast by host Sarah Koenig. That's the shortest way of describing what Serial is, without spoiling anything if you haven't yet listened. But this post isn't about the endless strings of conjecture, more about the phenomena of true crime obsession, and how this story is quietly changing the way we look at justice and starting real conversations.

I'm sure by now, most of you have either binge-listened or at least heard of the podcast phenomena that is Serial. Birthed from the wonderful nerdtopia radio series This American Life, Serial focuses on a single story, reexamining the details and the people involved, done with the intent of providing fresh new answers. Inevitably, it creates more questions and gives us all plenty to talk about. The first season -- free for download off iTunes or the Serial site -- was about a murder of a young high school girl named Hae Min Lee in 1999, in Baltimore, Maryland. Adnan Syed, her ex-boyfriend, was investigated based on a friend, Jay, who claimed Syed came to him to help bury Lee's body. Syed refutes Jay's account and says Jay's story is a total fabrication, he had nothing to do with her murder, and a confusing web of accounts over his whereabouts and motives are all explored in the 12-part podcast by host Sarah Koenig. That's the shortest way of describing what Serial is, without spoiling anything if you haven't yet listened. But this post isn't about the endless strings of conjecture, more about the phenomena of true crime obsession, and how this story is quietly changing the way we look at justice and starting real conversations.

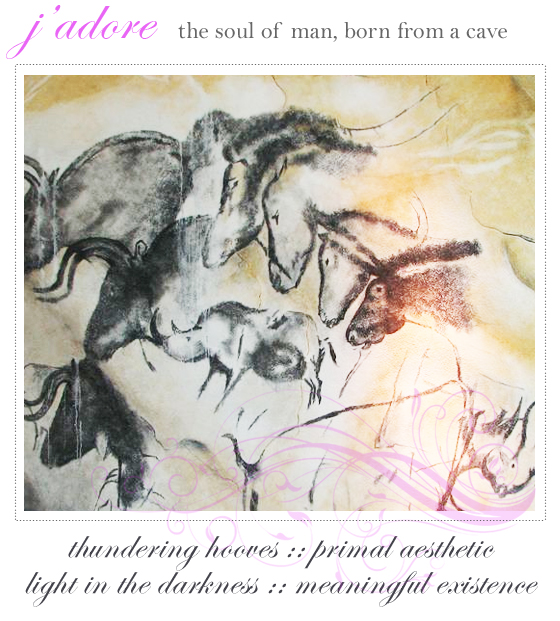

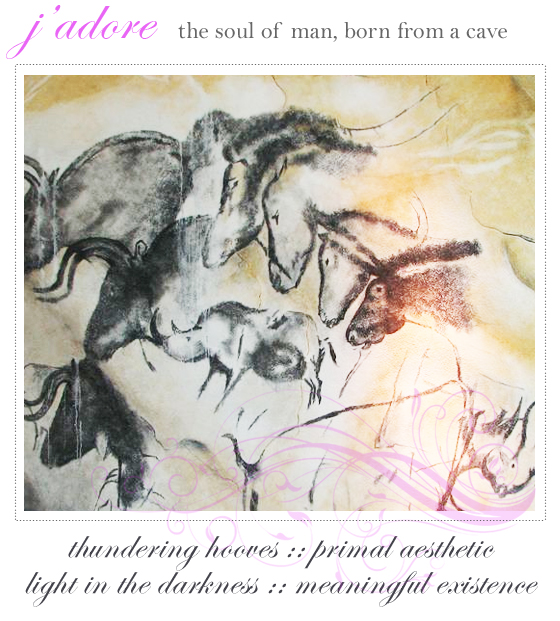

This Bird would be the first to say she's a skeptic over the fad of 3D making a comeback in theaters (Jaws III, anyone?), but in the case of Werner Herzog's documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, I'm happy to be wrong and thrilled to absorb every dimension of this amazing film. It's currently being shown in limited release, but only in 3D, so yes, you have to pay a few extra bucks and wear the Ray Ban-looking glasses, but don't worry, everyone else has to wear 'em too, and it literally brings the exploration of the Chauvet cave drawings to life.

The discovery of the Chauvet Pont-d'-Arc Cave happened several years ago in 1994, by rock climbers exploring the limestone walls along the Ardeche River in southern France. The cave had collapsed many ages ago, but the explorers were able to crawl through the tunnels of calcified rubble and discover some of the oldest cave drawings ever found. It was a significant piece of human history made even more priceless by the fact that the cave's collapse helped preserve the drawings perfectly. Like opening a time capsule over tens of thousands of years old, the scratchings and scrapings of soot across the rock walls are eerily undisturbed. An ice age come and gone, civilizations built and destroyed, world wars spreading across the continent, and yet the drawings look freshly-made. The documentary directed and narrated by the avant-garde director Werner Herzog is a rare glimpse of the Chauvet cave's interior. To preserve the integrity of the drawings and the cave itself, access is extremely limited, so this film is significant for anthropological purposes as it is a soulful journey looking into the early developments of humanity.

The long, slow paning of the camera thoughtfully captures the drawings of horses, lions and rhinos, concentrated in scenes that suggest hunting or perhaps symbolic offerings to early shamanistic beliefs. The drawings are layered in fluid, elegant strokes and shaded-in with charcoal while following the natural contours of the rock, made that much more visceral as you view it through the 3D glasses. Every curve of rock, married with the artful and voluminous shading suggests a level of sophisticated technique unexpected of prehistoric humans. While carbon dating confirm these drawings were done eons ago, it takes the soul of an artist like Herzog to explore the significance of these drawings and translate their beauty into the query of who we are today as a civilization.

His narration is slowly-paced, whimsical at times and then deliberately silent, to allow a moment of self-discovery to take place when viewing this message from the past. Herzog uses interviews from scientists and anthropologists to frame the biggest question, which is more rhetorical than anything else: is this where the human soul was born? Through art and culture, did early humans start to think more abstract, outside of the world they could see, and start to look inward, seeking a sense of meaning beyond basic nourishment and shelter. It's difficult to not be haunted by the beauty of the cave art, the delicate line quality and the symbolic nature of some of the drawings. It suggests an understanding of greater forces at work, even at those developmental stages of the species. It suggests that humans were perhaps always hardwired for faith and the need to seek out the divine.

While the film may seem slow in parts, or too deliberate in its need to absorb every drop of the cave's mystery, it echoes that scientific need to cover every milimeter of space and map out its potential for understanding. The Chauvet Cave's story is told in an almost mythic fashion, pieced together from different narrative sources, but not trying to produce a clear-cut answer. There simply isn't one, and there is no way to truly understand the mind of the artists behind these drawings. But the familiarity with the forms, the universal appreciation of its aesthetic qualities suggest a language that surpasses the barrier of time, that to marvel at its beauty is to tap into a deeply-ingrained language from within one's soul. To quietly ponder prehistoric drawings, even through the futuristic lens of 3D glasses in a theater, it evokes a spiritual dialogue that has no words, only the steady rhythm of a synchronous heartbeat in the darkness of a cave.

Jaunty Fine Print: photo from Wikipedia

This Bird would be the first to say she's a skeptic over the fad of 3D making a comeback in theaters (Jaws III, anyone?), but in the case of Werner Herzog's documentary, Cave of Forgotten Dreams, I'm happy to be wrong and thrilled to absorb every dimension of this amazing film. It's currently being shown in limited release, but only in 3D, so yes, you have to pay a few extra bucks and wear the Ray Ban-looking glasses, but don't worry, everyone else has to wear 'em too, and it literally brings the exploration of the Chauvet cave drawings to life.

The discovery of the Chauvet Pont-d'-Arc Cave happened several years ago in 1994, by rock climbers exploring the limestone walls along the Ardeche River in southern France. The cave had collapsed many ages ago, but the explorers were able to crawl through the tunnels of calcified rubble and discover some of the oldest cave drawings ever found. It was a significant piece of human history made even more priceless by the fact that the cave's collapse helped preserve the drawings perfectly. Like opening a time capsule over tens of thousands of years old, the scratchings and scrapings of soot across the rock walls are eerily undisturbed. An ice age come and gone, civilizations built and destroyed, world wars spreading across the continent, and yet the drawings look freshly-made. The documentary directed and narrated by the avant-garde director Werner Herzog is a rare glimpse of the Chauvet cave's interior. To preserve the integrity of the drawings and the cave itself, access is extremely limited, so this film is significant for anthropological purposes as it is a soulful journey looking into the early developments of humanity.

The long, slow paning of the camera thoughtfully captures the drawings of horses, lions and rhinos, concentrated in scenes that suggest hunting or perhaps symbolic offerings to early shamanistic beliefs. The drawings are layered in fluid, elegant strokes and shaded-in with charcoal while following the natural contours of the rock, made that much more visceral as you view it through the 3D glasses. Every curve of rock, married with the artful and voluminous shading suggests a level of sophisticated technique unexpected of prehistoric humans. While carbon dating confirm these drawings were done eons ago, it takes the soul of an artist like Herzog to explore the significance of these drawings and translate their beauty into the query of who we are today as a civilization.

His narration is slowly-paced, whimsical at times and then deliberately silent, to allow a moment of self-discovery to take place when viewing this message from the past. Herzog uses interviews from scientists and anthropologists to frame the biggest question, which is more rhetorical than anything else: is this where the human soul was born? Through art and culture, did early humans start to think more abstract, outside of the world they could see, and start to look inward, seeking a sense of meaning beyond basic nourishment and shelter. It's difficult to not be haunted by the beauty of the cave art, the delicate line quality and the symbolic nature of some of the drawings. It suggests an understanding of greater forces at work, even at those developmental stages of the species. It suggests that humans were perhaps always hardwired for faith and the need to seek out the divine.

While the film may seem slow in parts, or too deliberate in its need to absorb every drop of the cave's mystery, it echoes that scientific need to cover every milimeter of space and map out its potential for understanding. The Chauvet Cave's story is told in an almost mythic fashion, pieced together from different narrative sources, but not trying to produce a clear-cut answer. There simply isn't one, and there is no way to truly understand the mind of the artists behind these drawings. But the familiarity with the forms, the universal appreciation of its aesthetic qualities suggest a language that surpasses the barrier of time, that to marvel at its beauty is to tap into a deeply-ingrained language from within one's soul. To quietly ponder prehistoric drawings, even through the futuristic lens of 3D glasses in a theater, it evokes a spiritual dialogue that has no words, only the steady rhythm of a synchronous heartbeat in the darkness of a cave.

Jaunty Fine Print: photo from Wikipedia

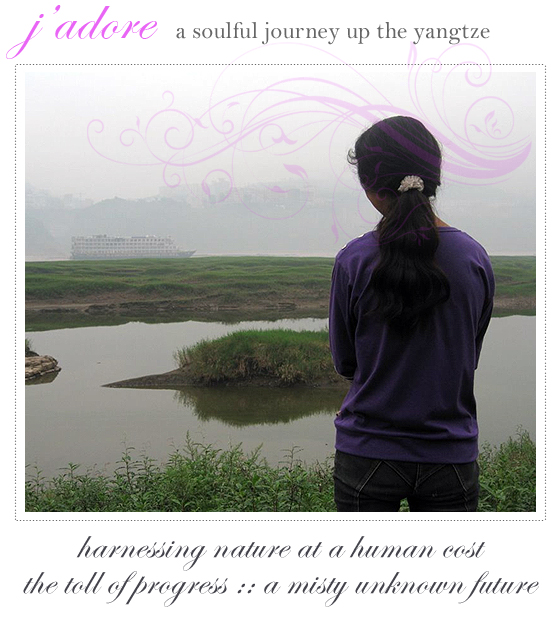

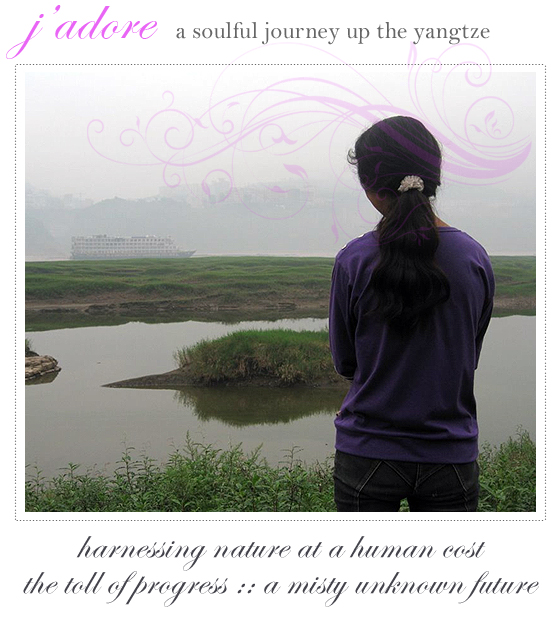

This Bird has always been fascinated by the sparkling truth of documentary films, as they highlight a little detail in the fabric of daily life, one that's often overlooked by the news, which seems to focus on singular cataclysmic events that are for the most part, momentary. Documentarians like Michael Moore gets a bit gonzo at times, so I've been gravitating towards smaller films that appear quiet on the surface, but a swirl of human debate lies below the calm. I remember seeing a preview for filmmaker Yung Chang's documentary, Up the Yangtze

This Bird has always been fascinated by the sparkling truth of documentary films, as they highlight a little detail in the fabric of daily life, one that's often overlooked by the news, which seems to focus on singular cataclysmic events that are for the most part, momentary. Documentarians like Michael Moore gets a bit gonzo at times, so I've been gravitating towards smaller films that appear quiet on the surface, but a swirl of human debate lies below the calm. I remember seeing a preview for filmmaker Yung Chang's documentary, Up the Yangtze , several years ago and was immediately haunted by the visuals of a mythically beautiful river cutting through deep valleys enrobed in mist, set against the contemporary issue of progress's path as it brings China into the 21st Century.

Chang's story focuses on the consequences of China's Three Gorges Dam, a longtime project originally conceived during the days of Chairman Mao, and now reaches fruition in our current century. The dam's purpose is to harness the great Yangtze River and convert it into hydroelectric energy, addressing China's need for resources as a growing global power. Not all of its rural cities have electricity and the country still relies heavily on coal-burning; the need for alternative energy sources has been a longtime question weighing on the nation as a whole, and the Three Gorges Dam is one potential answer. It's an epic feat of engineering, but takes a steep human toll -- as a result of the dam and re-routing the river's flow, it's caused the water level to rise and flood many riverside cities, resulting in two million people being uprooted. Livelihoods have been lost for those who farmed on the river's banks, and many have been forcibly moved without proper recompensation from the government. The issue is monumental, there is no clear resolution, and the documentary Up the Yangtze offers small glimpses into a handful of lives that are directly affected by the dam and the future it promises.

The most poignant figures in the film are the Yu family, and their daughter Yu Shui, barely fourteen and having to take a job on one of the tourist cruise ships that ferry Western visitors up the river, wanting to see the lands before the Yangtze swallows them up forever. Yu Shui's parents are poor subsistence farmers, living on the river's edge with no electricity, but using the land to provide their food. The slowly rising water threatens to engulf their home, so they know it is only a matter of time before they must relocate, but that means moving into a city apartment at a higher cost of living, which they can't afford without having land to farm. It's a terrible Catch-22 the family faces, so this leads them to the reluctant and ironic decision to send their eldest daughter, Yu Shui, to get a job on the cruise ship and hopefully provide enough income to both support the family and her own dream to get a university education. You can't help but cringe at moments where the Western tourists dress up in silly costumes of imperial Chinese royalty for photos and eat like kings in the massive cruise ship dining hall. And then you see Yu Shui -- given a Westernized name, Cindy, like all the workers on the ship -- talking to her parents and marveling at being able to have the luxury of meat more than once a week. The job provides "Cindy" a steady income along with English lessons, things that could keep a roof over her family's head and potentially propel her own future, but at the cost of her personal identity and the adoption of Western consumerism habits that may spend the money before she has a chance to send it home.

Up the Yangtze paints a very real picture of China as a nation, not the pastoral landscape the government-run tourism industry would prefer the world to see. Not to say it's a completely unflattering portrait -- it's beautiful in its complexity, heartbreakingly poignant in the loss of history in the name of evolution, and unflinchingly handsome in its reality. There is no simple answer, and all you can do is weep for those who are crushed under the heavy wheel of progress, and wish good fortune on the next generation who will hopefully bring a better future for this rapidly-changing nation. It's a great documentary because it doesn't provide a clear resolution, merely provoke the deeper issue everyone must come to terms with regarding the Devil's bargain of economic passage and the inevitable toll it takes on humanity.

Jaunty Fine Print: photo from Up the Yangtze website

, several years ago and was immediately haunted by the visuals of a mythically beautiful river cutting through deep valleys enrobed in mist, set against the contemporary issue of progress's path as it brings China into the 21st Century.

Chang's story focuses on the consequences of China's Three Gorges Dam, a longtime project originally conceived during the days of Chairman Mao, and now reaches fruition in our current century. The dam's purpose is to harness the great Yangtze River and convert it into hydroelectric energy, addressing China's need for resources as a growing global power. Not all of its rural cities have electricity and the country still relies heavily on coal-burning; the need for alternative energy sources has been a longtime question weighing on the nation as a whole, and the Three Gorges Dam is one potential answer. It's an epic feat of engineering, but takes a steep human toll -- as a result of the dam and re-routing the river's flow, it's caused the water level to rise and flood many riverside cities, resulting in two million people being uprooted. Livelihoods have been lost for those who farmed on the river's banks, and many have been forcibly moved without proper recompensation from the government. The issue is monumental, there is no clear resolution, and the documentary Up the Yangtze offers small glimpses into a handful of lives that are directly affected by the dam and the future it promises.

The most poignant figures in the film are the Yu family, and their daughter Yu Shui, barely fourteen and having to take a job on one of the tourist cruise ships that ferry Western visitors up the river, wanting to see the lands before the Yangtze swallows them up forever. Yu Shui's parents are poor subsistence farmers, living on the river's edge with no electricity, but using the land to provide their food. The slowly rising water threatens to engulf their home, so they know it is only a matter of time before they must relocate, but that means moving into a city apartment at a higher cost of living, which they can't afford without having land to farm. It's a terrible Catch-22 the family faces, so this leads them to the reluctant and ironic decision to send their eldest daughter, Yu Shui, to get a job on the cruise ship and hopefully provide enough income to both support the family and her own dream to get a university education. You can't help but cringe at moments where the Western tourists dress up in silly costumes of imperial Chinese royalty for photos and eat like kings in the massive cruise ship dining hall. And then you see Yu Shui -- given a Westernized name, Cindy, like all the workers on the ship -- talking to her parents and marveling at being able to have the luxury of meat more than once a week. The job provides "Cindy" a steady income along with English lessons, things that could keep a roof over her family's head and potentially propel her own future, but at the cost of her personal identity and the adoption of Western consumerism habits that may spend the money before she has a chance to send it home.

Up the Yangtze paints a very real picture of China as a nation, not the pastoral landscape the government-run tourism industry would prefer the world to see. Not to say it's a completely unflattering portrait -- it's beautiful in its complexity, heartbreakingly poignant in the loss of history in the name of evolution, and unflinchingly handsome in its reality. There is no simple answer, and all you can do is weep for those who are crushed under the heavy wheel of progress, and wish good fortune on the next generation who will hopefully bring a better future for this rapidly-changing nation. It's a great documentary because it doesn't provide a clear resolution, merely provoke the deeper issue everyone must come to terms with regarding the Devil's bargain of economic passage and the inevitable toll it takes on humanity.

Jaunty Fine Print: photo from Up the Yangtze website